You can also listen to an audio version of this post on The Signal Podcast on Anchor, Spotify, and iTunes.

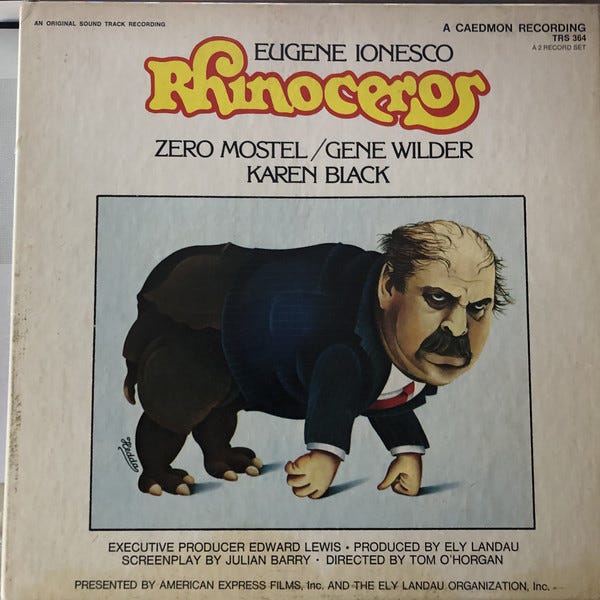

It has been over sixty years since Romanian-Franco playwright Eugene Ionesco wrote his absurdist tragicomedy Rhinoceros, and nearly fifty years since Gene Wilder and Zero Mostel helped bring the parable about the perils of ideology and group-think to the silver screen.

And still it seems we have learned little from the landmark work of absurdism. Like his one act The Leader, Ionesco’s most famous work has a lot to say about leadership and sensemaking.

For those who haven’t seen a production of this quintessential theatre of the absurd play or the Mostel/Wilder film, the story centers on an apathetic drunkard named Bérenger who lives in a rural French village where the people are slowly transforming into rhinoceroses. He loses his best friend to the epidemic, and eventually his love interest. And at the end, he is the last human being, having resisted succumbing to the lure of conforming with the rest of the community who are rampaging through town, ostensibly destroying civilization as the curtain falls.

Ionesco wrote the play to address a burning post-World War II question. How did countries like France and Romania capitulate to Nazi Germany?

Ideology as Virus

Living in his native Romania in the early 1940s, Ionesco saw many of his neighbors abandon their principles to join the Nazi movement in order to conform to a popular ideology sweeping the country. A similar phenomenon occurred in France, whose government capitulated to Nazi forces in 1940. Drawing on this experience, his play depicts ideology like a contagion or virus that invisibly spreads through the population.

This is similar to the ideological state apparatus proposed by neo-Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser. He asserted that the ideological state apparatus is composed of media and educational institutions which are charged with indoctrinating the public into particular ideologies that benefit the state. He would have pointed to capitalist ideology in the United States as an example. But the same could be said about socialist ideology in the Soviet Union. Or whatever the dominant ideology is in any society.

Rhinoceros has often been described as a play about nonconformity, which was probably why it was so appealing as a film in the early 1970s during the height of the counterculture movement. But it is also a play about the dangers of ideology - that invisible, mind altering collection of ideas that shape a society and culture - which can lead to inhuman violence.

As an example, here is a clip from the beginning of Zero Mostel’s transformation into a rhinoceros from the 1973 film. He seems like he has caught a flu with his sore throat and abnormal pulse, but he has really been infected with ideology.

Ideological Polarization and Splintering

Several years ago, before the pandemic, I tried to mount a fringe production of Rhinoceros to explore the polarized, ideological divide in America. I wanted to see if there was a way to depict the polarization in the US by creating two different types of rhinoceros on stage to represent the extremist ideologies on the far left and the far right. Sadly, I wasn’t able to mount it.

Who knows if I would have been able to pull it off? The script may resist such a staging. But one thing is for sure - the polarization I wanted to explore with the play has only grown worse. Not only are the polarities on either side of the ideological spectrum becoming more extreme, but they also seem to be splintering into smaller, niche camps. There are now even people who identify as radical centrists and the political homeless. It’s a motley mix of warring camps.

We have all bore witness to this on social media As we have all learned by now, early juggernauts like Facebook and Twitter designed their platforms to exacerbate the partisan and ideological divide we are now seeing -left/right/radical center, pro-COVID vaccination/ anti-COVID vaccination/ anti-MAGA/pro-MAGA, pro-Woke/anti-Woke.

But now instead of the warring factions creating their ideological bubbles on these major platforms, they are splintering off into their own platforms like Parler and GETTR. These isolated echo chambers will reinforce the group-think already polarizing the country. This will likely produce irrational thinking based on poor sensemaking. And this may have violent repercussions like those we saw during the January 6 assault on the US capitol and the relentless season of violent protests in Portland, Oregon last year. We all have watched the results of this polarized, ideological mob mentality on our TV screens over the past few years - and its priming up to get worse as everyone sequesters into their bubbles.

Mob Mentality and the French Film Noir Panique

Like everything, this phenomenon exists on a spectrum. On the most basic level, there is the classic mob mentality where the public gets caught up in a frenzy based on poor sensemaking of a situation.

Again, the French provide us with a perfect example of the dangers of the mob mentality with the 1946 noir film Panique (Panic) by director Julien Duvivier. A woman is murdered in a small town. People speculate about who may have done it. A man already disliked because of his appearance is framed by the actual murderer by planting a rumor that spreads through town at the velocity only emotionally charged misinformation can spread. At the end, the villagers chase down the innocent man to his death during a harrowing rooftop scene.

Coming out of the fog of World War II, many artists tackled the question of how groupthink could lead to horrific violence like the Holocaust. So, it is no coincidence that the innocent man in the film goes by the name of M. Hire, but his real name is revealed to be Hirovitch, a Jewish name. It is easy to get the mob to scapegoat a person who is already part of the out group.

As Kenneth Turan describes the character in his Los Angeles Times review of the film.

“Nattily dressed with a thick full beard, Hire is something of a standoffish fussbudget. An amateur photographer who documents human misery and orders the bloodiest meat possible from the local butcher, he gives the neighborhood the creeps, and it is easy to see why.”

Panique is a film noir parable about how mob mentality can lead to the death of an innocent outcast due to a rumor, but Rhinoceros takes it a step further to demonstrate how ideology can destroy civilization itself. One would think we would have evolved beyond this as a society, but it seems like it is becoming worse than ever if the trends on social media are any indication.

During this era of ideological polarization, people are offering up several new terms to describe this phenomenon. Some that have been used are the Egregore and Mass Formation Psychoises.

The Egregore - Updating an Occult Concept

The Egregore concept comes from the occult and describes a non-physical entity that arises from the collective consciousnesses of a group of people. In the classic sense, it is a thought form that relies on the devotion of the group, performed through rituals and sacrifice. Even though it is born from a collection of minds, it develops its own autonomy, influencing the thoughts of the group of people that brought it into existence.

Not being a believer in the occult, I share that etymological information to lay the foundation for how the term is beginning to be used in the modern context. Today, Egregore is used to describe entities like corporations, fandoms, or ideological tribes. The collective entity created by the minds of those involved with it becomes more than the sum of its parts.

It’s perceived autonomy comes from the complexity produced by its interaction with so many minds. Those who believe in this concept say that the egregore evolves and changes based on its mental interactions with the collective. To preserve itself, it can jettison old ideas and upload new ones as it continues to influence the collection of minds connected to it. It’s sort of like a description of ideology in the cloud computing age.

Mass Formation Psychosis

More recently, Dr. Robert Malone, guest on the Joe Rogan podcast, stirred up controversy by introducing the term Mass Formation Psychosis to describe the phenomenon of collective, orthodox thinking around COVID-19 vaccinations. Many media outlets began to discredit his statements by saying there is nothing about Mass Formation Psychosis in the psychological literature.

Those publications miss the point. The term’s grounding in the psychiatric and sociological literature notwithstanding, he is employing the term to describe the same characteristics of ideology that Ionesco tried to warn us about.

It’s easy to dismiss his proposal due to the inflammatory terms he used to name it. Psychosis in this case seems pejorative much like Trump derangement syndrome. And Dr. Malone clearly possesses an anti-COVID vaccine bias, but as we have seen, his concerns about the dangers of some kind of orthodox group-think are not limited to him.

We probably have evolution to blame for this. It is natural for humans to be tribal. We are pack animals. No wonder we get along so well with dogs. We want that companionship. That sense of belonging. That confirmation of a shared reality.

The Final Act - Lonely Leadership

In the final act of Rhinoceros, Bérenger engages in a personal battle over whether to conform and become a rhinoceros or remain human. The language he uses to frame his conflict is revealing. He describes the rhinoceros as beautiful and sees his own human reflection in the mirror as ugly.

We can see the allure to conforming to a group in that dichotomy. Even though to an audience watching at a distance, the rhinoceros in the play seems monstrous and terrifying, the characters see whatever the creature represents as seductive. It possesses the allure of community and belonging and a clear, unambiguous reality. Yet, its rigid, gray body and violent temperament also represent the danger of calcified, group-think - ideology turning the mind into a rigid and destructive monster.

Leaders in sensemaking roles need to resist the lure of ideology. As Ionesco’s absurdist parable shows, joining the group-think can be seductive. People confirm and reward your thinking. It provides a comfortable and stable reality. It makes you feel good.

The harder job is to be like Bérenger and resist those seductive impulses to join the group - no matter how appealing the ideology. And as more fragmentation occurs and more discrete ideological camps form, it is going to be imperative for leaders to engage in rigorous sensemaking to understand the reality of complex situations. Rigid ideology creates too many blind spots, distorting our perceptions of the world.

Unfortunately, those who do this may end up in the loneliest of places as the rest of the various rhino herds trample through the streets tearing down civilization. But as lonely as those leaders may be, at least they will have their integrity…and the truth.